| Early days | Maritime Life | Sperry Univac |

| NS Credit Union League | Xerox, COS | Scotiatech |

|

I got a job at Scotiatech, in the Annapolis Valley of Nova Scotia. Scotiatech was the Information Technology department of Scotia Investments, the holding company of the Jodrey family. Scotiatech provided services to: |

J'ai trouvé un emploi chez Scotiatech, dans la vallée d'Annapolis en Nouvelle-écosse. Scotiatech était le département des technologies de l'information de Scotia Investments, la société de portefeuille de la famille Jodrey. Scotiatech offrait des services à : |

|

Scotiatech programmers and analysts were assigned to projects at the various companies, as needed. This environment provided rich opportunities for involvement in manufacturing, inventory control, order processing, and telecommunications.

|

Les programmeurs et analystes de Scotiatech étaient affectés à des projets au sein des différentes entreprises, selon les besoins. Cet environnement offrait de nombreuses possibilités de s'impliquer dans les domaines de la fabrication, de la gestion des stocks, du traitement des commandes et des télécommunications. |

|

|

A few Scotiatechers at racquetball tournament. Top: Terry Dulong, a Rectal Orifice, Yvonne Van Blarcom Mid: Ann Jardine, Lorraine Banks, Gordon Cumming, Dave Frizzell Bot: Pierre Clouthier, Peter Gesner |

|

My first project was at COBI Foods. We evaluated, selected and implemented an order entry & inventory system. We rejected BPCS (Business Process Control System), in favour of the more comprehensive PMS (Product Management System), which was written in RPG, and ran on an IBM System 38, later AS/400. We were able to combine the inventories and sales reporting for the Graves, Avon and Stokely-Van Kamp brands, which had up to then been kept separate. I went on to manage the telecommunications network for the combined companies. We used the Datapac service, an X.25 packet-switching network. Datapac was a cost-effective way of connecting branches across the country to the head office computer. We were able to run HP and IBM traffic on the same line. I wrote a program in QBASIC to monitor the network status. Called NIPS (Network Integrity and Performance System), it polled the X.25 PADs (Packet Assembler/Disassembler) and switches to check that they were running OK. It ran on an XT, a 4 MHz PC. A PAD converted Asynch traffic to X.25 packets. I was often required to visit remote sites to diagnose and fix faults in the communications systems. My patient wife would accompany me. I would optimistically under-estimate the repair time, and she would chide me about the "Scotiatech 15 minutes", code-word for an interval of understated and interminable duration. Most of the other companies used HP 3000 systems written in COBOL or RPG. I also evaluated and selected a computer system for Armour Transport when they took over the management of Pole Star. We found an excellent system called LTL/400 written by Reeve Fritchman, who lived in Philadelphia at the time. LTL is trucking lingo for "Less than Truckload", payloads that don't fill a trailer, and require assembling many loads to be cost-effective. As the IT capabilities of the SIL companies grew increasingly sophisticated, they formed their own IT departments, and Scotiatech was dissolved and the employees laid off. |

Mon premier projet s'est déroulé chez COBI Foods. Nous avons évalué, sélectionné et mis en œuvre un système de saisie des commandes et de gestion des stocks. Nous avons rejeté le BPCS (Business Process Control System) au profit du PMS (Product Management System), plus complet, écrit en RPG et fonctionnant sur un IBM System 38, devenu par la suite AS/400. Nous avons ainsi pu fusionner les stocks et les rapports de vente des marques Graves, Avon et Stokely-Van Kamp, qui étaient jusqu'alors gérés séparément. J'ai ensuite pris en charge la gestion du réseau de télécommunications des entreprises fusionnées. Nous utilisions le service Datapac, un réseau à commutation de paquets X.25. Datapac offrait une solution économique pour connecter les succursales à travers le pays au siège social. Nous pouvions ainsi faire transiter le trafic HP et IBM sur la même ligne. J'ai développé un programme en QBASIC pour surveiller l'état du réseau. Appelé NIPS (Network Integrity and Performance System), il interrogeait les PAD (Packet Assembler/Disassembler) et les commutateurs X.25 afin de vérifier leur bon fonctionnement. Le système fonctionnait sur un XT, un PC de 4 MHz. Un convertisseur analogique-numérique (PAD) convertissait le trafic asynchrone en paquets X.25. Je devais souvent me rendre sur des sites distants pour diagnostiquer et réparer les pannes des systèmes de communication. Ma patiente épouse m'accompagnait. J'avais tendance à sous-estimer le temps de réparation, ce qui lui valait des reproches, notamment concernant les « 15 minutes Scotiatech », une expression désignant un intervalle interminable et pourtant sous-estimé. La plupart des autres entreprises utilisaient des systèmes HP 3000 programmés en COBOL ou RPG. J'ai également évalué et sélectionné un système informatique pour Armour Transport lors de la reprise de la gestion de Pole Star. Nous avons trouvé un excellent système, le LTL/400, développé par Reeve Fritchman, qui vivait alors à Philadelphie. LTL, dans le jargon du transport routier, signifie « Less than Truckload » (chargement partiel), désignant des chargements qui ne remplissent pas une remorque et qui nécessitent le regroupement de plusieurs chargements pour être rentables. à mesure que les capacités informatiques des sociétés SIL se perfectionnaient, elles ont formé leurs propres départements informatiques, et Scotiatech a été dissoute et ses employés licenciés. |

|

I incorporated my company, Kyber Consulting, and did a couple of very interesting projects, while beginning the development of what later became Progeny's Charting Companions, genealogy graphics software. |

J'ai créé ma société, Kyber Consulting, et réalisé quelques projets très intéressants, tout en commençant le développement de ce qui allait devenir plus tard Progeny's Charting Companions, un logiciel de graphisme généalogique. |

|

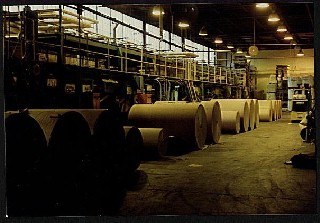

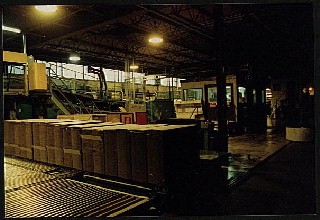

MPP makes cardboard, using huge rolls of linerboard made by Minas Basin. They have a plant in Dartmouth, NS. The carboard is manufactured in a continuous process by a Marquip corrugating machine. The Marquip is the length of a football field, and costs about $1M. Typically, three rolls of linerboard are fed into the corrugator. The centre roll is rippled or corrugated, giving the cardboard its rigidity. The three layers are glued together.

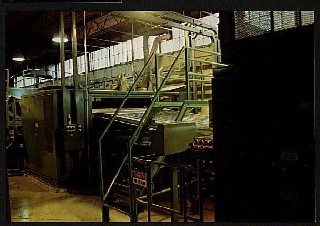

The web of cardboard travels quite fast. It is slit longitudinally by wheel knives, and cut cross-wise by a knife specially spiralled around a long metal bar. The width of the cardboard is determined by the position of the wheel knives, and the length by the frequency of rotation of the cross-knife. These are controlled by an AT PC (8 MHz). |

MPP fabrique du carton à partir d'immenses rouleaux de carton de couverture produits par Minas Basin. Son usine est située à Dartmouth, en Nouvelle-écosse. La fabrication du carton se fait en continu grâce à une onduleuse Marquip. Cette machine, de la longueur d'un terrain de football, coûte environ un million de dollars. Généralement, trois rouleaux de carton de couverture sont introduits dans l'onduleuse. Le rouleau central est ondulé, ce qui confère au carton sa rigidité. Les trois couches sont ensuite collées ensemble. La bande de carton défile rapidement. Elle est fendue longitudinalement par des couteaux rotatifs, puis coupée transversalement par un couteau enroulé en spirale autour d'une longue barre métallique. La largeur du carton est déterminée par la position des couteaux rotatifs, et sa longueur par la fréquence de rotation du couteau transversal. Ces paramètres sont contrôlés par un automate programmable ATPC (8 MHz). |

|

|

| Rolls of liner board prepared for loading | Slitter station |

|

The dimensions can be entered by the employees that operate the corrugator. MPP wanted to automatically transfer the information directly from their customer order system, which ran on an HP 3000, to the Marquip PC. I accepted the assignment as an independant contractor. |

Les dimensions peuvent être saisies par les opérateurs de l'onduleuse. MPP souhaitait transférer automatiquement ces informations directement de son système de gestion des commandes clients, fonctionnant sur un HP 3000, vers le PC Marquip. J'ai accepté cette mission en tant que consultant indépendant. |

|

|

| Cross-cut and stacker | Finished product |

|

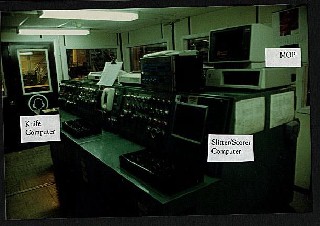

I wrote MOP (Marquip Order Program) in Borland C. MOP ran on the Marquip PC, and was connected to the HP via an RS-242 Asynch line. I wrote a low-level interrupt handler to communicate with the HP. MOP logged on to a port on the HP, and simulated a human operator inquiring about an order. The PC would retrieve all the data: carton width, height, quantity, customer name, etc. It would write the information to a disc file, which was then picked up by the Marquip control program. This freed the operators to concentrate on the complexities of managing the Marquip, and reduced transcription orders. |

J'ai programmé MOP (Marquip Order Program) en Borland C. MOP fonctionnait sur le PC Marquip et était connecté au HP via une liaison RS-242 asynchrone. J'ai développé un gestionnaire d'interruptions bas niveau pour communiquer avec le HP. MOP se connectait à un port du HP et simulait un opérateur humain consultant une commande. Le PC récupérait toutes les données : largeur et hauteur du carton, quantité, nom du client, etc. Il enregistrait ces informations dans un fichier disque, qui était ensuite pris en charge par le programme de contrôle Marquip. Cela permettait aux opérateurs de se concentrer sur la gestion complexe du Marquip et réduisait le nombre de commandes saisies. |

|

| Control room |

|

MPP also wanted to print shipping labels, in large, visible letters. I reverse-engineered font outlines from the Borland library, and adapted them to a dot-matrix printer. I implemented the rarely-used output buffer interrupt to compensate for the slow printer speed. When most Asynch applications need to output on a COM port, they just test whether the port is free, and loop until the previous characters are transmitted and the the port is available. This is called polling. After all, what else is there to do while waiting for the output to complete? In a mutli-tasking environment such as MOP, this was not acceptable as the PC had to be continuously available for other tasks. So after outputting a character, I would resume operations, and wait for the output buffer interrupt to inform me that the output port was available again, whereupon the program would interrupt what it was doing and fire off another character. Debugging interrupts was tricky business. You couldn't stop the program, or print out trace data, which would have been too slow. This was a DOS application, so we were limited to 640K, which wasn't enough memory to store thousands of real-time memory snapshots. The PC had 2MB of actual memory, inaccessible due to DOS' limitations. Fortunately, there was a trick which enabled the computer to treat the high-order memory as a 'disc'. The program could open a virtual file, write ot it, then later read it back. I stored high-speed debugging trace statements in this manner. MOP ran reliably for many years. |

MPP souhaitait également imprimer des étiquettes d'expédition en gros caractères bien visibles. J'ai donc reconstitué les contours des polices à partir de la bibliothèque Borland et les ai adaptés à une imprimante matricielle. J'ai implémenté l'interruption du tampon de sortie, rarement utilisée, pour compenser la faible vitesse d'impression. La plupart des applications asynchrones, lorsqu'elles doivent écrire sur un port COM, vérifient simplement sa disponibilité et bouclent jusqu'à ce que les caractères précédents soient transmis et que le port soit libre. C'est ce qu'on appelle l'interrogation. Après tout, que faire d'autre en attendant la fin de l'écriture ? Dans un environnement multitâche comme MOP, cette approche était inacceptable, car le PC devait rester disponible pour d'autres tâches. Ainsi, après l'écriture d'un caractère, je reprenais les opérations et attendais que l'interruption du tampon de sortie m'informe de la disponibilité du port. Le programme interrompait alors son exécution et envoyait le caractère suivant. Le débogage des interruptions était complexe. Il était impossible d'arrêter le programme ou d'imprimer les données de trace, ce qui aurait été beaucoup trop lent. Il s'agissait d'une application DOS, ce qui limitait la mémoire à 640 Ko, insuffisante pour stocker des milliers d'instantanés mémoire en temps réel. Le PC disposait de 2 Mo de mémoire vive, inaccessibles en raison des limitations de DOS. Heureusement, une astuce permettait à l'ordinateur de traiter la mémoire vive comme un disque. Le programme pouvait ouvrir un fichier virtuel, y écrire des données, puis les relire ultérieurement. J'ai ainsi stocké des traces de débogage à haute vitesse. MOP a fonctionné de manière fiable pendant de nombreuses années. |

|

Larsen Packers is a hog slaughterhouse in Berwick. They buy hogs from local pig farmers, cut, process and package the meat for sale to consumers. The processing of hogs includes weighing the carcass after it has been gutted and cleaned, and measuring the percentage of fat and meat. This is done with a probe shaped like a gun with a long needle. At the tip of the needle is a photocell that can detect white fat and pink meat. The carcasses are hung from hooks that travel along an overhead conveyor line, and pass in front of each station where an operator performs a task. Each hog is tatooed at birth with the farmer's number. As the hogs travel down the line, they are weighed on an electronic scale, then an operator probes the flank, where the meat/fat content is transmitted electronically. |

Larsen Packers est un abattoir de porcs situé à Berwick. L'entreprise achète des porcs auprès d'éleveurs locaux, les découpe, les transforme et conditionne la viande pour la vente aux consommateurs. La transformation des porcs comprend la pesée de la carcasse après éviscération et nettoyage, ainsi que la mesure du pourcentage de gras et de viande. Cette opération est réalisée à l'aide d'une sonde munie d'une longue aiguille. à l'extrémité de l'aiguille se trouve une cellule photoélectrique qui détecte le gras blanc et la viande rose. Les carcasses sont suspendues à des crochets qui se déplacent le long d'un convoyeur aérien et passent devant chaque poste de travail où un opérateur effectue une tâche. Chaque porc est marqué au tatouage à la naissance avec le numéro de l'éleveur. Au fur et à mesure de leur progression sur la chaîne, les porcs sont pesés sur une balance électronique, puis un opérateur effectue une palpation du flanc, permettant ainsi la transmission électronique des données relatives à la teneur en viande et en gras. |

|

| Probing meat |

|

Previously, Larsen would print the information on a strip of paper, and then key it in manually. They wanted to automate and speed up the process. They retained my services to develop GPI - Grading Probe Interface. (My only regret is not having named it 'PIG': Probe Interface for Grading). GPI used the communications interrupt handler I had developed for MPP. It ran on a 386, and communicated simultaneously with the electronic scale, the probe gun, the keyboard and a bar code scanner. It used a special communications board that added 8 Asynch ports to the PC. The information was merged into a single record, written to diskette at the end of a shift, then brought to an IBM AS/400 to calculate the amounts owed to each farmer. The probe gun was interesting. It was manufactured in New Zealand, and used a current loop interface. It had the ability to display a six-digit number at the end facing the operator, which came in handy for synchronizing the weighing and probing. This number originated from GPI, and required using the gun's special communications protocol. The whole process had unique challenges and pressures. Since the hogs were cut up, it was impossible to re-do a run if the data were lost. This would have been catastrophic as Larsen's could not re-create the information, and would have had to estimate, certainly to the detriment of one or other party. As a precaution, the data was written to two separate files. Each file was closed and re-opened after each transaction, to flush the buffer and prevent a loss if the power failed or the program crashed. The data was also printed in real-time as a backup. The first day we went live was interesting. Larsen was too cheap to pay the employees for training. We did a few tests with a single carcass, during which I once got my hardhat knocked off by a swinging hog. But there was never a full-scale rehearsal because it would have involved twenty or thirty highly-paid unionized employees, and many expensive hogs. So we implemented the system cold turkey. Picture this: I'm standing next to the operator at the weigh/probe station. At the other end of the line, the hog carcasses start rolling in from the kill station. In the first step, an operator directs a big propane flame at the carcass, burning off the hairs. The smell of burnt hair fills the hall. And here I am quickly teaching this guy, whom I've never met, how to operate this complex new computer system. Remember, these guys don't slaughter hogs because they are whizzes at business systems. We have a couple of minutes before the first big, 400-lb carcass comes swinging at us. Here it comes! Quickly we spike a bar code on the carcass, wait for the weighing, stick the probe in, done! Whew! Then along comes the next one. Zero margin for error. What a circus. We only had to abort the run once. The next time we pulled it off. This was one of the most nerve-wracking IT episodes in my life. But I did enjoy the project immensely, and the Larsen's staff, including Frank Weir and Barry Fowlow, were great people to work with. I built my own protocol analyzer by making a split cable, writing a special program that ran on a 286, and displaying in hex the stream of bytes flowing over communications port. I also wrote a simulator for the scale and the probe, enabling me to debug GPI in my office in the trailer I had installed next to my home on the North Mountain. The program was very stable. The only time I was called in for maintenance was to compensate for an operator who insisted on jigging the bar code label under the scanner. |

Auparavant, Larsen imprimait les informations sur une bande de papier, puis les saisissait manuellement. L'entreprise souhaitait automatiser et accélérer le processus. Elle a fait appel à mes services pour développer GPI (Grading Probe Interface). (Mon seul regret est de ne pas l'avoir appelée « PIG » : Probe Interface for Grading). GPI utilisait le gestionnaire d'interruptions de communication que j'avais développé pour MPP. Fonctionnant sur un 386, il communiquait simultanément avec la balance électronique, le pistolet de pesage, le clavier et un lecteur de codes-barres. Il utilisait une carte de communication spéciale ajoutant huit ports asynchrones au PC. Les informations étaient fusionnées en un seul enregistrement, écrites sur disquette à la fin de chaque poste, puis transférées vers un IBM AS/400 pour calculer les montants dus à chaque agriculteur. Le pistolet de pesage était intéressant. Fabriqué en Nouvelle-Zélande, il utilisait une interface à boucle de courant. Il pouvait afficher un nombre à six chiffres à son extrémité, face à l'opérateur, ce qui s'avérait très pratique pour synchroniser la pesée et le palpage. Ce numéro provenait de GPI et nécessitait l'utilisation du protocole de communication spécifique de l'arme. L'ensemble du processus présentait des défis et des contraintes uniques. Les porcs étant découpés, il était impossible de recommencer une opération en cas de perte de données. Cela aurait été catastrophique, car Larsen's n'aurait pas pu reconstituer les informations et aurait dû procéder à des estimations, certainement au détriment de l'une ou l'autre des parties. Par précaution, les données étaient enregistrées dans deux fichiers distincts. Chaque fichier était fermé puis rouvert après chaque transaction afin de vider le tampon et d'éviter toute perte en cas de coupure de courant ou de plantage du programme. Les données étaient également imprimées en temps réel à titre de sauvegarde. Le premier jour de mise en service fut mémorable. Larsen's était trop radin pour payer la formation de ses employés. Nous avons effectué quelques tests avec une seule carcasse, au cours desquels un porc m'a fait perdre mon casque. Mais il n'y a jamais eu de répétition générale, car cela aurait impliqué une vingtaine ou une trentaine d'employés syndiqués très bien payés, et de nombreux porcs coûteux. On a donc mis en place le système du jour au lendemain. Imaginez la scène : je suis à côté de l’opérateur au poste de pesage/sondage. à l’autre bout de la chaîne, les carcasses de porc commencent à arriver de l’abattoir. Première étape : un opérateur brûle les poils de la carcasse avec une grosse flamme de propane. L’odeur de poils brûlés emplit le couloir. Et moi, je suis là à expliquer en vitesse à ce type que je ne connais pas comment se servir de ce nouveau système informatique complexe. Faut pas oublier que ces gars-là ne sont pas des as de l’informatique à abattre des porcs. On a quelques minutes avant que la première grosse carcasse de 180 kg ne nous fonce dessus. La voilà ! On colle vite fait un code-barres dessus, on attend la pesée, on insère la sonde, et hop ! Ouf ! Et puis arrive la suivante. Zéro marge d’erreur. Quel cirque ! On n’a eu à interrompre la production qu’une seule fois. La fois suivante, on a réussi. Ce fut l'un des épisodes informatiques les plus stressants de ma vie. J'ai cependant énormément apprécié ce projet, et l'équipe de Larsen, notamment Frank Weir et Barry Fowlow, était formidable. J'ai construit mon propre analyseur de protocole en fabriquant un câble divisé, en écrivant un programme spécifique fonctionnant sur un 286 et en affichant en hexadécimal le flux d'octets transitant par le port de communication. J'ai également développé un simulateur pour la balance et la sonde, ce qui m'a permis de déboguer le protocole GPI depuis mon bureau aménagé dans la caravane près de ma maison, sur la Montagne du Nord. Le programme était très stable. La seule fois où j'ai été appelé pour la maintenance, c'était pour dépanner un opérateur qui s'obstinait à manipuler l'étiquette du code-barres sous le scanner. |

|

MT&T (later Aliant) is one of the telcos (telephone companies) that provides telephone services in Canada. When a customer leases a data communication line from a telco, the line often crosses more than one provincial jurisdiction. When there is a problem and the communications link is down, the telcos collaborate to fix it. The customer need only talk to the telco where the customer's head office is located, and the latter coordinates fixing the problem. When the customer notifies his telco, a trouble ticket is created which registers the complaint. In 1991, Canadian telcos developed a system to swap trouble tickets. Each telco had their own administrative system, so they each developed their own versions. MT&T called theirs RIC (Resource Interface Converter). I sub-contracted to DDA to write RIC in C, running under IBM's OS/2. RIC was connected to the IBM mainframe using APPC (Advanced Peer-toPeer Communications) . The RIC PC also had an X.25 card, connected to the Datapac network. RIC would submit queries to the IMS data base. When a trouble ticket was opened, RIC would retrieve the information, re-format it, and transmit it to the other province over Datapac. RIC would also poll the national network for incoming trouble tickets, which were posted to MT&T's data base. OS/2 was 5 years ahead of Microsoft Windows, and offered full 32-bit processing long before Windows did. However, OS/2's strength was also its weakness. OS/2 was developed from scratch, and was not encumbered a legacy of DOS compatibility, 16-bit applications, and drivers like Windows was. This enabled IBM to innovate radically and more quickly. RIC was a multi-threaded program, written paradoxically with Microsoft's Programmer Workbench, the character-based precursor to Visual Studio. However, this freedom from legacy code also meant there were few applications available for OS/2, and the only drivers were for IBM printers. OS/2 eventually disappeared in spite of its technological superiority at the time. IBM's development environment was called C-Set, and, in spite of being a 32-bit compiler, was inferior to Programmer's Workbench. For instance, after a compliation, if you double-clicked on an error message, it would open up the source code in a separate editor window, in a proportional typeface. You could not trigger a compilation from this window. You had to make your change, save & close, then go back to the compiler window. Retarded. There was no Resource Workshop for designing dialog boxes visually. You had to write all the statements in a text editor, and wouldn't see the appearance until compiling and running the program. This slowed down development. While debugging, I recall trying to step into the GUI part of the application code. This locked up the computer so bad we had to re-install OS/2, a tedious process requiring 22 diskettes. The IBM documentation was so inscrutable that even for ver. 2 of OS/2, we had to refer to Microsoft's ver. 1 manuals. IBM's support gave an interesting insight into OS/2's downfall. MT&T had an expensive OS/2 support contract with IBM. The MT&T contacts were two guys in the PC support section. When I required technical support to answer some obscure and specialized questions about OS/2, it didn't make sense to get the MT&T guys involved, even though they were supposed to be the only offical go-between with IBM. So I called IBM with MT&T's authorization, and impersonated one of the support techs. After a few calls I slipped and used my name. The IBM guy was livid and tore a strip of me, saying that as an independant contractor, I had no business blah blah. Here I was just trying to get a customer up & running. The MT&T people I worked with, such as Fraser Smith, Ken Goodick and Ron Jordan, were friendly and smart, a pleasure to work with. |

MT&T (devenue Aliant par la suite) est l'une des entreprises de télécommunications fournissant des services téléphoniques au Canada. Lorsqu'un client loue une ligne de communication de données auprès d'un opérateur, cette ligne traverse souvent plusieurs provinces. En cas de problème et d'interruption de la liaison, les opérateurs collaborent pour le résoudre. Le client n'a qu'à contacter l'opérateur de la province où se situe son siège social, qui se charge de coordonner la résolution du problème. Lorsque le client signale un incident à son opérateur, un ticket d'incident est créé pour enregistrer la réclamation. En 1991, les opérateurs canadiens ont développé un système d'échange de tickets d'incident. Chaque opérateur disposant de son propre système administratif, ils ont développé leur propre version. MT&T a nommé la sienne RIC (Resource Interface Converter). J'ai sous-traité à DDA le développement de RIC en C, fonctionnant sous OS/2 d'IBM. RIC était connecté à l'ordinateur central IBM via APPC (Advanced Peer-to-Peer Communications). Le PC du RIC était également équipé d'une carte X.25, connectée au réseau Datapac. Le RIC interrogeait la base de données IMS. Lorsqu'un ticket d'incident était ouvert, le RIC récupérait les informations, les reformatait et les transmettait à l'autre province via Datapac. Le RIC interrogeait également le réseau national pour les nouveaux tickets d'incident, qui étaient ensuite enregistrés dans la base de données de MT&T. OS/2 avait cinq ans d'avance sur Microsoft Windows et offrait un traitement 32 bits complet bien avant Windows. Cependant, la force d'OS/2 était aussi sa faiblesse. OS/2 a été développé de A à Z et n'était pas encombré par la compatibilité DOS, les applications 16 bits et les pilotes hérités de Windows. Cela a permis à IBM d'innover radicalement et plus rapidement. Le RIC était un programme multithread, paradoxalement écrit avec Microsoft Programmer Workbench, l'environnement de programmation en mode texte précurseur de Visual Studio. Cependant, cette absence de code hérité impliquait également un nombre limité d'applications disponibles pour OS/2, et les seuls pilotes existants étaient destinés aux imprimantes IBM. OS/2 a fini par disparaître malgré sa supériorité technologique de l'époque. L'environnement de développement d'IBM s'appelait C-Set et, bien qu'étant un compilateur 32 bits, il était inférieur à Programmer's Workbench. Par exemple, après une compilation, un double-clic sur un message d'erreur ouvrait le code source dans une fenêtre d'éditeur séparée, avec une police proportionnelle. Impossible de lancer une nouvelle compilation depuis cette fenêtre : il fallait effectuer les modifications, enregistrer et fermer, puis revenir à la fenêtre du compilateur. Absurde ! Il n'existait pas d'Atelier de ressources pour concevoir visuellement les boîtes de dialogue. Il fallait écrire toutes les instructions dans un éditeur de texte et ne voir le résultat qu'après compilation et exécution du programme. Cela ralentissait considérablement le développement. Lors d'un débogage, je me souviens avoir essayé d'accéder à la partie interface graphique du code de l'application. L'ordinateur était tellement bloqué que nous avons dû réinstaller OS/2, une opération fastidieuse qui a nécessité 22 disquettes. La documentation IBM était si obscure que même pour la version 2 d'OS/2, nous avons dû consulter les manuels de la version 1 de Microsoft. Le support IBM nous a permis de mieux comprendre les raisons du déclin d'OS/2. MT&T avait un contrat de support OS/2 onéreux avec IBM. Les interlocuteurs chez MT&T se limitaient à deux personnes du service support PC. Lorsque j'ai eu besoin d'assistance technique pour répondre à des questions pointues et techniques sur OS/2, il était absurde de faire intervenir les techniciens de MT&T, même s'ils étaient censés être le seul interlocuteur officiel auprès d'IBM. J'ai donc appelé IBM avec l'autorisation de MT&T et me suis fait passer pour l'un des techniciens. Après quelques appels, j'ai commis l'erreur de donner mon nom. L'employé d'IBM était furieux et m'a passé un savon, m'accusant, en tant que prestataire indépendant, de ne pas être à ma place. Je cherchais simplement à aider un client à utiliser son système. Les personnes de MT&T avec lesquelles j'ai travaillé, comme Fraser Smith, Ken Goodick et Ron Jordan, étaient sympathiques et intelligentes ; c'était un plaisir de travailler avec eux. |

| << Xerox, COS | Back to the Rants |